Programming and Human Languages

Have you ever thought how programming languages relate to one another? I recently did, and to my surprise there is a lot of similarities with human languages.

I’m sure you will see programming languages in a different way after reading this. If you don’t know much about programming, this will help you understand them a bit more.

First things first, what is a programming language?

I won’t go into defining what a human language is, because I assume we already have a common understanding. But what is a programming language?

According to wikipedia: “a programming language is a formal language that specifies a set of instructions that can be used to produce various kinds of output.” This is a good formal definition, but there are other aspects I want to consider. The main purpose of a programming language is to “transfer information into a computer”, with the goal of the computer producing a result. And here is where I find the first analogy. What is the main purpose of a human language? Well, I would say it is to “transfer information into a human”. In the same way that the receiving human needs to understand the human language, a computer running code needs to interpret the programming language. Luckily for them, it's easy for them to understand new languages by installing software.

Other than the core purpose of transferring information, there is a clear difference on how they operate. Programming languages are 100% logical (ok, 99% if we consider Heisenbugs). It may seem irrational when bugs appear, but there is always an underlying logical explanation. Everything a program does can be boiled down to 3 concepts: Inputs, State and Outputs. Inputs are the information given to run the program. State is the information existing within the system. And outputs are the information generated from the computation. All programs are structured like this, formed by submodules that interact with each other to create complex systems.

Humans arguably do this as well, if we consider senses inputs, memory state and actions outputs. But it’s not yet clear if we work like this at a fundamental level. I have talked about it before, and it’s an ongoing debate in fields such as philosophy and physics. This is also why I won’t be considering quantum computing in this article (that, and the fact that I don’t have experience with it).

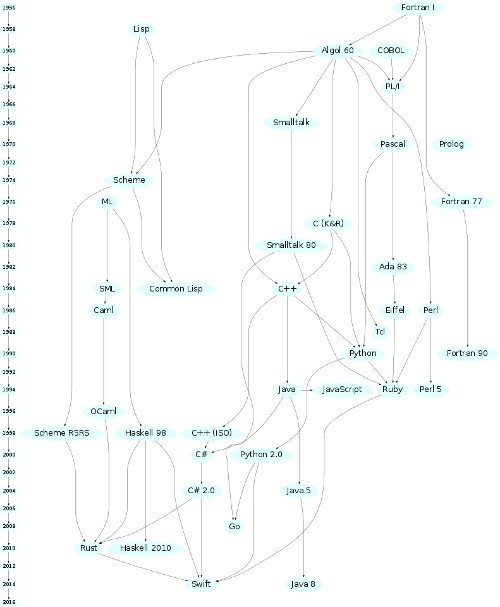

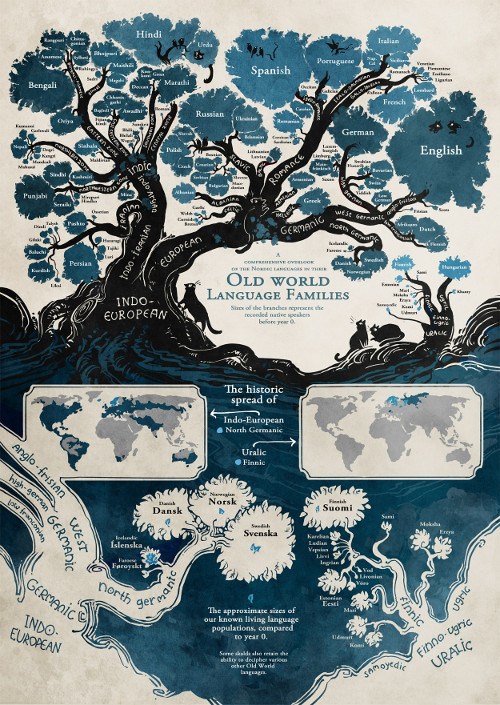

Languages birth

The first thing I want to talk about is how programming languages come into existence. Contrary to human languages that are created naturally, programming languages are created artificially, and there is a design process involving conscious decisions behind their creation. However, there is no programming language that comes out of nowhere. Similar to human languages, programming languages have a genealogy (family tree). Creating a new programming language always involves using existing concepts and ideas. One particularity is that their family tree is actually messier than the human languages’. Because they are often influenced by many others, they have multiple ancestors.

Here you can see an example to compare both genealogies (click to see more details):

If you are curious, the first programming language was Fortran, and it was born in 1954. So the history of programming languages is only about 64 years old.

Languages structure

When looking at programming languages, there is always an underlying structure that is common to all of them. All have variables, methods, loops, conditionals, etc. And the same can be said for human languages; all of them have verbs, adjectives, conjunctions, etc. It also goes beyond simple structural components; in programming we can find design patterns that can be used in any language, and with humans we find concepts like eating or feeling emotions common to everyone.

This bears to conclude that all languages stem from one abstract mother language. For humans, this is the mental model we all share regardless of culture and race. There is an hypothesis considering this which calls it language of thought. For programming it is called pseudocode, which is used to define code regardless of implementation and platform. This idea of having a mother language is further supported by the fact that they can be translated into one another. Human languages are constantly being translated, but programming languages are also translated with a process called compilation. At the end, anything can be implemented or said in any language, but each one is more suitable for a specific context. This explains why Eskimos have so many different words to say “snow”, or why Perl has so much string manipulation functionality.

Sounding native

Thinking about this concept of “sounding native” is what got me started thinking on this topic. Languages have syntax rules indicating what is correct and what isn't. And there are tools that can validate those. For humans we call them spell checkers and for programming they are called linters.

But there are also non-written rules that vary from one context to another and aren't standard. And that’s something remarkable, because the same thing happens with human speech. I could speak in Spanish with a Mexican and we’d understand each other perfectly. But we’d both notice many subtle differences that give away that we are not native from the same context. One stark example in programming is tabulations, some languages tend to use 2 spaces instead of 4 (or, god forbid, tabs). If you ever want to become fluent in a language, keep this in mind. Small subtleties make all the difference.

An extension to this can be found in dialects. When a human language changes too much, we call it a dialect. In some occasions, speaking a language is not enough to understand other dialects. For programming we find this behavior with frameworks. Being written with the same language, the differences can still make it hard for a developer to understand the code.

Languages proliferation

Something definitely different is the pace at which they are created. As I commented before, the first programming language appeared 64 years ago. In only those few years, programming languages' count could be about to surpass human languages'. According to this article, it is possible that we already have more programming than human languages. And according to this other article, Python is apparently the most popular language to be taught in primary schools (including human languages). I have to be skeptic about those, but keep in mind that they were published in 2009 and 2015 respectively. Today this may be an exaggeration. But if they keep this pace, in another 64 years programming languages will have surpassed human languages for sure. I wouldn’t be surprised if 50 years from now people who don’t know to code are like people who don't know how to read today. Programming is definitely the new literacy.

One possible explanation for this phenomenon is how easy it is to learn new languages. We already established how computers can learn new programming languages just by installing software, but for humans it isn’t that difficult either. If I count, I would say I know about 8 programming languages, while I only speak 3 human languages. I have been studying a new human language for more than a year, and I’m barely getting started. But I can learn a new programming language quite thoroughly in less than a month. Learning a new programming language is often easier than people think.

Another possible explanation is how easy it is to create a new programming language. There is even a category of programming languages that are literally created without purpose, called esoteric programming languages. One I find particularly amusing is Taxi; a programming language that consists on a virtual taxi moving “data passengers” from one place to another in order to execute operations.

Languages usage

Tying into this we can talk about how they are used. When choosing a programming language, there is a saying of choosing “the right tool for the job”. This tries to convey that programming languages are not better nor worse, but more appropriate depending on the task at hand. But that statement is only true in theory. In practice, there are other reasons why someone would choose one language over another. I would argue the strongest arguments for picking a language to use are the languages you already know and how many people are using it. Again, we find the same pattern for human languages, and it’s more extreme given the complexity to learn a new language. It’s obvious that a person will prefer to work with others speaking the same language, or learn one that many others speak.

This becomes crystal clear when looking at the current trends of programming languages.

Let’s talk about the king: Javascript

Javascript was originally created for the web, and its main purpose was to make websites (the front-end) more dynamic. But fast-forward to today, and people is writing software using Javascript everywhere: Front-end, Backend (Node.js), Mobile (Ionic), Desktop (Electron), etc. And I have something to confess: I used to hate Javascript.

One of the slides in a talk I gave in 2017.

I’m probably not the only one who did. In university, I learned programming using Java and C++; and going to Javascript after that was not a nice experience (specially back in 2011). Fortunately, things are looking much better today.

But the reason for this to happen is not that Javascript was a great language at the beginning. This happened because it is the most accessible language. Everyone has everything they need to learn and run Javascript code: a browser. The popularity of Javascript is tied in no small measure to the growth of the Web. And the open source movement has made it even more accessible, given that it is the most used language in GitHub repositories.

Conclusion

After this, I’m sure you see programming in a different light, regardless of your previous background with it. At first glance it may seem stiff and boring, but it can be one of the most creative activities that you will find. I certainly think that, and it plays a big part on why I love programming so much. The same program can be implemented in a thousand different ways, and choosing one is part of the craft. This is something Linus Torvalds refers to as having good taste. And let me finish with something you may not realize: naming things is the most difficult thing programmers have to do. Let that sink in.